Something which, in our study and consideration of language, strikes us as an interesting point, is the value (or lack of value) we place on some words, and indeed the positive (and negative) attitudes we have towards some words. Some words are less enjoyed, or are indeed abhorred; profanities, for example – think, ‘everyone’ has the same most hated – are just a series of letters as much as any other word, but our valuation of the word, proportional, it seems, to our use of it, has made it so much more severe. Stephen Fry provides some ridicule of the Watershed by noting that in everyday life we (rather overdramatically) place negative terms where they are not best used – ‘the traffic was murder this morning’, ‘this lecture is torture’, ‘the highstreet is dead today’ – and do not see the nonsense in this. Morover, we don’t feel any need for censorship in this – but, wait, we are talking about death, torture, murder, so… What’s more, Fry notes that even in doing this, we feel the need to wait until the dark of night to say, for example, ‘fuck’ (in a sexual context or otherwise) when the use of this and its brothers expresses genuine passion and intensity. How can we censor passion but not the thoughtless use of serious terms?

Statistics Mark One:

Thinking from here about the nature of potentially destructive language, and having discussed our favourite words and, perhaps more reluctantly, our hated ones, we considered language somewhat in relation to identity, asking the

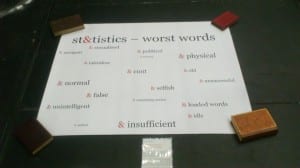

question ‘What is the Worst Word someone could use to describe you?’ Setting out a black box (calling to our aesthetic desires and designs, as ever – something referred to as ‘the insistence on the image’ in Theatre of Images Revisited by Klich and Scheer) we allowed people to write that which they consider to be the worst description someone could use for them and place it in the box. 107 responses came, bravely, from our peers adnwe chose to categorise them in order to move towards a format through which we could represent the statistics. Arguably, it would have been better to allow a cross-section of our peers to categorise the results themselves because they would then be reflecting on their contribution, rather than we as theatre-makers ma

nipulating something which we were only facilitating. Regardless of this, though, the piece – particularly the categorisation – was rather insightful.

Statistics Mark Two:

From the collection of the data we experimented with various ways of representing the statistics – perhaps a slightly crude way of considering people’s feelings about these words (and, by extension, themselves) but arguably all the more effective because the coldness of statistical representation is in such sharp contrast with the deeper meanings that the critique and message of the piece is all the more significant. Taking inspiration from visual representations of rape statistics which I came across via Tumblr (and which can be seen in original location here – http://www.circlesoffireproductions.com/2013/01/the-facts-about-rape-are-bad-enough/) I began to experiment with various ways to achieve the end goal – an attractive and clear presentation of the information which was still unusual enough to fit with the character of our piece. Our final presentation – red and black against a stark white background, and with ‘&’ as a frequent image (all of which is a continuous thread in Censored Sensibility) came together clearly and visually attractively, yet another contrast to the negativity of the work’s implications.

Statistics Mark Two-Point-Oh-No-Actually-Never-Mind:

After the collation of the first sets of data, we changed our box to read ‘What is your favourite word?’ While this was an interesting task and one which received many responses, to change to a positive idea, we felt, decreased the value of the first ‘Worst Word’ idea. An exploration of positive language tells us less about ourselves and our use of language and does not have the critical edge which we very much desired and which features in all of our installations. Perhaps a shame to waste it, but we feel it was better left alone. Nothing we do is an exact science, everything is Trial & Error, and if you don’t try you’ll never know.